PART 3: FIGHTING TO SERVE

Though Americans of all races jumped to contribute to the nation’s victory in World War II, the nation did not welcome all efforts.

The Chicago Defender, December 13, 1941; Video: The Negro Soldier (1944) from the National Archives

The Marine Corps did not permit African Americans to join until June of 1942.

Black men were allowed to serve in the Army and Air Force in 1941, but only in segregated units. There were more Black men who wanted to serve than there were all-Black units; when these units filled, hopeful soldiers were told there was no room for them.

—

Images:

1) Howard P. Perry was the first Black American to enlist in the Marine Corps (1942).

2) U.S. fighter pilots receive briefing for a mission at a base in Italy (Sept. 1944).

Source: National Archives

In the days after Pearl Harbor, hundreds of Black men were turned away by military recruiters.

“If it were a question of having a Marine Corps of 5,000 whites or 250,000 Negroes, I would rather the whites.”

Major General Thomas Holcomb, Commandant of the Marine Corps, 1942

The Navy enlisted Black men, but all Black naval workers were assigned to roles as messmen: cooks and waiters whose primary work was to serve white sailors.

Throughout the military, Black men were placed into support roles far more frequently than they were placed into combat roles.

Eugene Tarrant grew up in Dallas, Texas. When he joined the Navy at 18, he earned a near-perfect score on its aptitude test. Here, he describes his experience aboard the USS San Francisco:

“My job was to serve and take care of the officers. We had to clean their quarters, shine their shoes, serve their food. I mean actually serve it: set up the table and go to each one with a serving platter and extend it…

“I rebelled against it. I told them: I didn’t come into the Navy to do this, be a servant. I could’ve stayed in Dallas and done that.”

Source: The Digital Collections of the National WWII Museum (interview); Berkeleyside (image)

Black Americans had fought in every war since America’s founding. They were committed to fighting in World War II. Yet, racism and discrimination plagued every branch of the armed forces – the very forces fighting for freedom and democracy abroad.

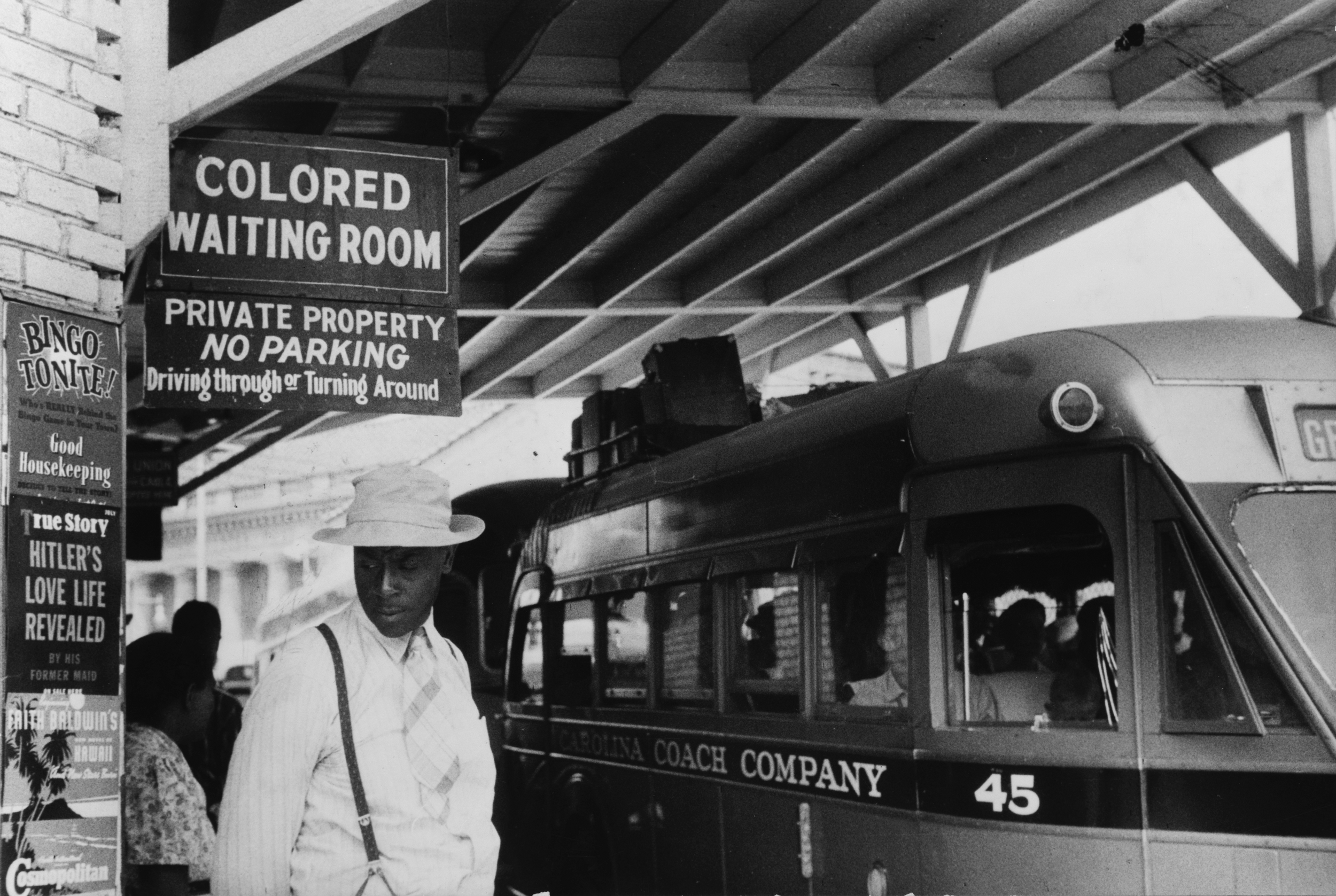

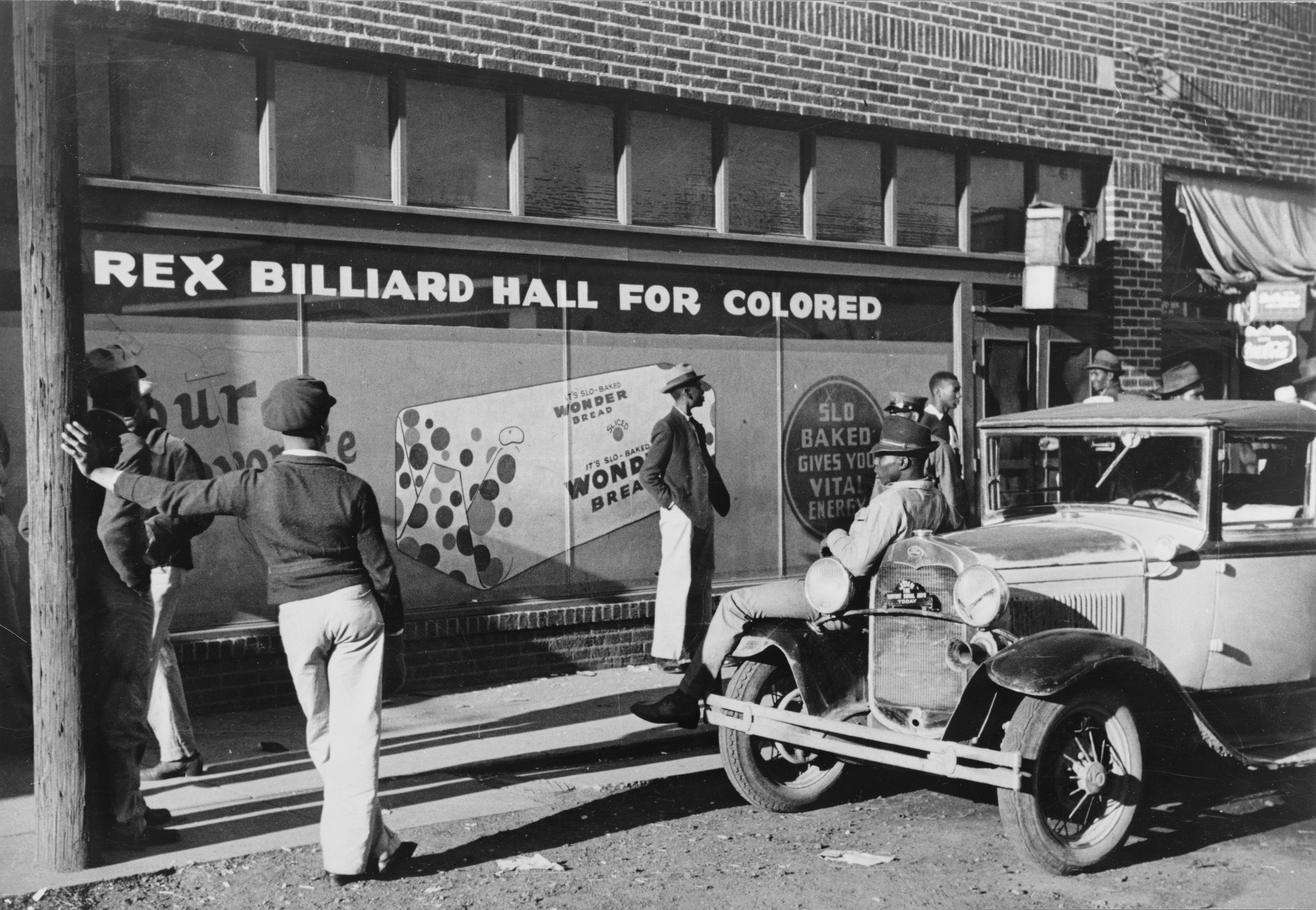

IN THE LAND OF JIM CROW

From the 1890s on, state and local governments in the south passed laws that demanded strict racial segregation, or separation, between Black and white Americans.

These laws stripped Black people from many of the rights they were promised as United States citizens. Black Americans paid taxes to fund public libraries, universities, and even swimming pools – but they were not allowed to patronize them.

Customs of segregation crept into every aspect of daily life, limiting where and how Black Americans could work, go to school, travel, shop for groceries, and eat lunch.

This system of discriminatory laws and customs came to be known as Jim Crow.

The Black Americans who did join the nation’s armed forces boarded trains for bases and training facilities, many of which were in the South.

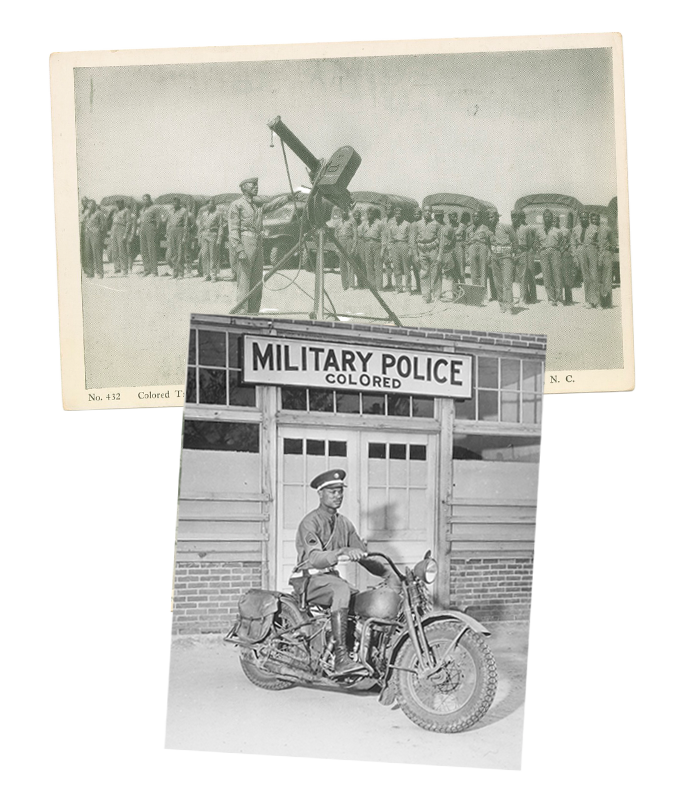

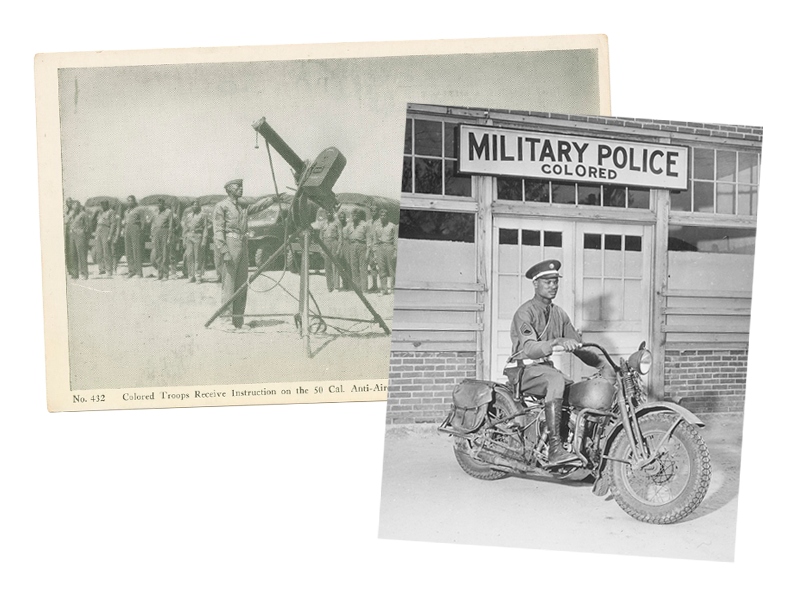

When men like Booker T. Spicely arrived at camps to train as United States soldiers, they served in all-Black units that were usually led by white commanding officers.

They slept in segregated barracks, healed their wounds in segregated hospital wards, rode segregated buses to segregated work assignments, and socialized in segregated settings.

—

Images:

1) An all-Black unit at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, learns how to operate an anti-aircraft machine gun.

2) A member of the Black military police in Columbus, Georgia (April 13, 1942).

Source: National Archives

Servicemen detailed their experiences of discrimination, abuse, and violence — both on military bases and off of them — to major publications and the nation’s most prolific Black leaders.

Thurgood Marshall (image) received many letters from Black servicemen. As the chief lawyer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (then the nation’s largest civil rights organization, more commonly known as the NAACP), Marshall criss-crossed the country during World War II investigating abuse and violence. The following excerpt from Matthew Delmont’s Half American: The Epic Story of African Americans Fighting World War II at Home and Abroad excerpts and summarizes a letter Marshall received from one soldier in 1941:

-

“I am taking it upon myself to write to you in the hope that something may be done to put a stop to the treatment of the Black troops now stationed at Camp Lee, Virginia,” wrote Sydney Rotheny, a member of the 9th Quartermaster Regiment. “The situation is getting very serious and I can truthfully say for myself and the other two thousand Black men now at Camp Lee, that we are getting very tired…”

Rotheny described a series of indignities: White officers slapped and threatened to kill Black enlisted men. On the bus into town, white soldiers demanded that Black soldiers give up their seats. To get back from town, white military police made Black soldiers wait in a separate line until all white soldiers boarded the bus. This meant Black soldiers sometimes waited an hour or more as bus after bus filled with white troops and motored back to camp. At the segregated post exchange, an overzealous white second lieutenant took it upon himself to ban the sale of Black newspapers. Throughout Camp Lee, Black soldiers were called racial epithets daily.

“Aren’t we supposed to be men?” Rotheny asked. “Yet we are treated like dogs.” The majority of Black troops at Camp Lee were drafted from cities in the north and west and were struggling to adjust to the Southern system of racial segregation they found on and off base. “It would be a pleasure soldiering for Uncle Sam if we were treated like humans,” he concluded, “but as things stand now, all we want is out, out of the Army and back to our homes.”

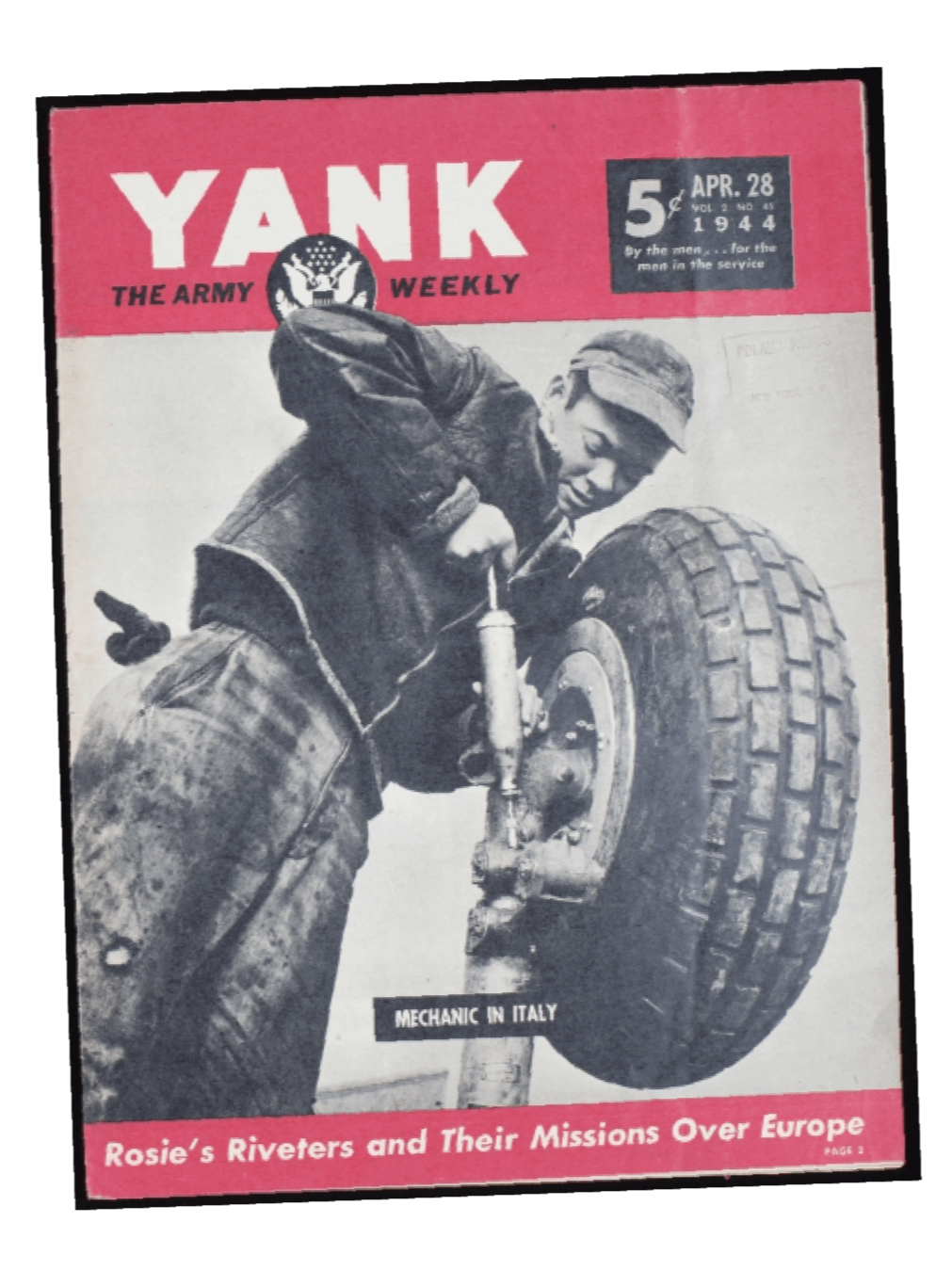

In 1944, Corporal Rupert Trimmingham wrote a letter to Yank, the weekly Army magazine, comparing the treatment of Black soldiers to that of Nazi prisoners of war:

-

“Myself and eight other soldiers were on our way from Camp Claiborne, La. to the hospital here at Fort Huachuca. We had to lay over until the next day for our train. On the next day we could not purchase a cup of coffee at any of the lunchrooms around there. As you know, Old Man Jim Crow rules. The only place where we could be served was at the lunchroom at the railroad station but, of course, we had to go into the kitchen. But that’s not all; 11:30 am about two dozen German prisoners of war, with two American guards, came to the station. The entered the lunchroom, sat at the tables, had their meals served, talked, smoked, in fact had quite a swell time. I stood on the outside looking on, and I could not help but ask myself these questions: Are these men sworn enemies of this country? Are they not taught to hate and destroy…all democratic governments? Are we not American soldiers, sworn to fight for and die if need be for this our country? Then why are they treated better than we are? Why are we pushed around like cattle?”

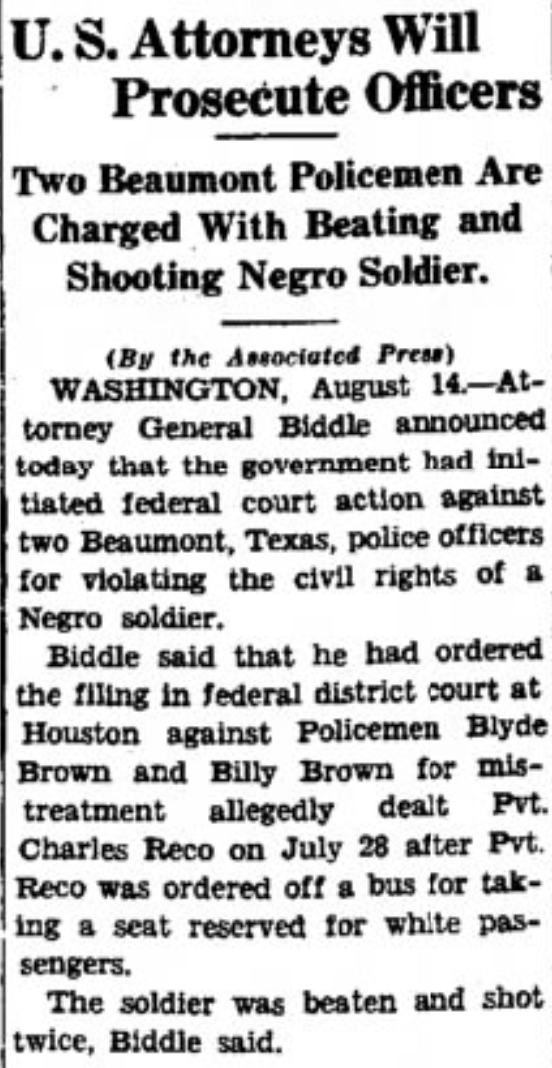

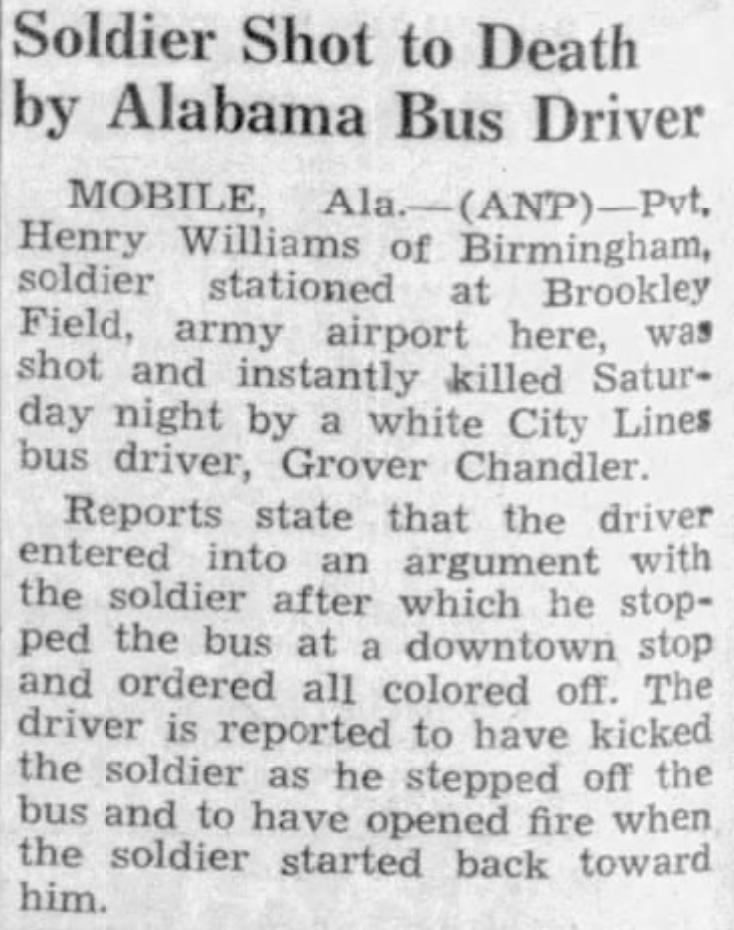

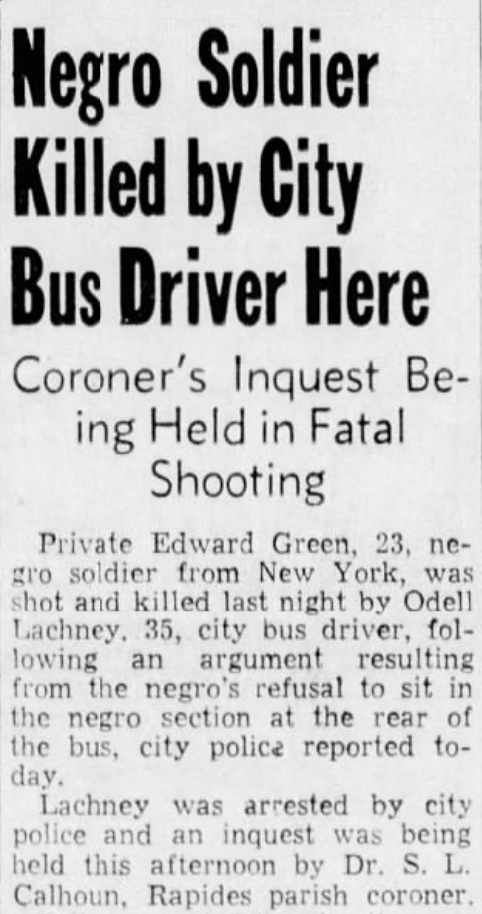

From 1941 to 1946, there were at least 50 documented racially motivated homicides of Black soldiers and veterans by whites in the United States.

-

The Marshall News Messenger (Marshall, Texas), Jan. 11, 1942

-

The Chillicothe Constiution-Tribune (Chillicothe, Mo.), Aug. 14, 1942

-

The Afro-American (Baltimore, Md), Aug. 29, 1942

-

Alexandria Daily Town Talk (Alexandria, La.), March 14, 1944

-

The Durham Herald-Sun (Durham, N.C.), July 9, 1944